This is the third blog article in a new series on the innovation of political parties.

To bring about change in a political party, new ideas must be aspired to, sourced, assessed, evolved, implemented, and scaled. But for every great idea, there are dozens of other ideas that prove to be less valuable. Thus, to increase the likelihood of finding a great idea, it is important to source as many ideas as possible – in innovation, the more, the better. But where do these ideas come from?

Our second blog article on how political parties can be strategic about innovation has already indicated that strategically managing ideas makes political parties more successful. Therefore, we want to dive a little deeper into elaborating on what this actually means.

Firstly, we will introduce the reader to our model of how innovative ideas emerge in political parties. Then we focus on the importance of empowering innovators to bring their ideas on the table of party leadership.

The sources of innovative ideas in political parties

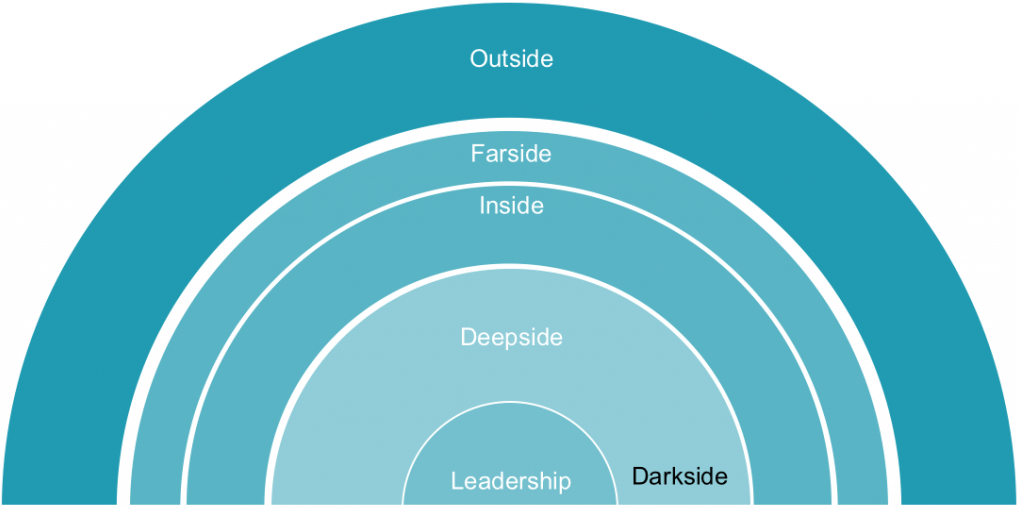

Traditionally, the so-called “theory of closed innovation” relied on the fact that the research and development process took place within organisational boundaries. As Henry Chesbrough, an American organisational theorist at Berkeley, expanded the limits of that classical model and developed the theory of “Open Innovation”: innovative ideas do not only stem from people inside of an organisation, but also from external sources, like customers and partners. As you can see in our model below, this applies to political parties, as well.

First, innovative ideas may come from outside the party. Examples are organisations such as think tanks or partner organisations, other political parties, or concepts already in use in the business world. Using the ideas from the party’s ecosystem is what we call “outside-innovation”.

Second, innovative ideas may originate from within the party. In this case, it is often intrapreneurs (e.g. party officials, staff) who push and implement innovations. This is what we call “inside-innovation”. But also party members, volunteers and activists can contribute ideas if they are given the opportunity, e.g. through discussions at the party’s general meetings or via online collaboration tools. This is what we call “farside-innovation”.

And third, innovative ideas may also come from informal power structures within political parties. If this is, for example, a regional party chair or regional prime minister who has a strong influence on the party, we call it “deepside-innovation”. If this refers to an unseen but close circle around party leadership (e.g. personal advisors or trusted people), we call that “darkside-innovations”, as those operating there are often less visible than in the other circles.

Sometimes, the party leader her/himself or the party board can be the source of innovation. This is what we call “centre-innovation”.

Bringing ideas from inside and outside to the centres of parties

Great ideas can help political parties bring about change in policy, organisation, and behaviour. But to ensure the implementation of great ideas, they need leadership attention.

Political parties are complex, hard to manage, and not agile. Harald Katzmair, Executive Director of FASresearch and political thinker (in Josef Lentsch: Political Entrepreneurship) argues that this leads to highly centralised power structures where everyone orients themselves towards the centre. These structures are less and less capable of using the knowledge produced inside or outside the organisation. Thus when innovating in a political party, two aspects need to be considered:

First, executives must establish processes and/or programmes that empower innovators to bring their ideas on the table of party leadership. This may take the form of, for example, open innovation efforts to develop a new party programme, idea competitions to identify best practice for events and campaigning, or introducing new positions that push internal reform efforts.

Second, managers need to build inclusive decision-making processes to prevent relevant players from sabotaging their innovation efforts. To do this, innovators must think about how they can build positive relations with the deepside, as well as with the darkside.

In our next blog article, we will analyse the obstacles that prevent the implementation of new ideas.