ABOUT NEW FORMS OF PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY IN OUR CITIES

A big task lies ahead of us. We are building the European Capital of Democracy initiative and we are in it for the long haul. Each European Capital of Democracy will be the centre of a positive discourse about democracy by showcasing new methods of decision making and policy creation at city level. Starting in autumn 2021, every year a different European city will be designated the European Capital of Democracy so it may inspire others to follow suit.

Just now, democracy is being threatened and, at the same time, promoted as never before. As a matter of fact, many European cities have not been idle, and a process of rethinking and redoing democracy is already underway.

On 18 September 2020, we launched the European Capital of Democracy initiative with a distinguished line-up of democratic leaders from all over Europe. In three round table discussions, they shared crucial aspects that are key to strengthening democracy at all levels, local, national and European. We therefore want to dedicate a series of blog articles to examine these aspects in more detail.

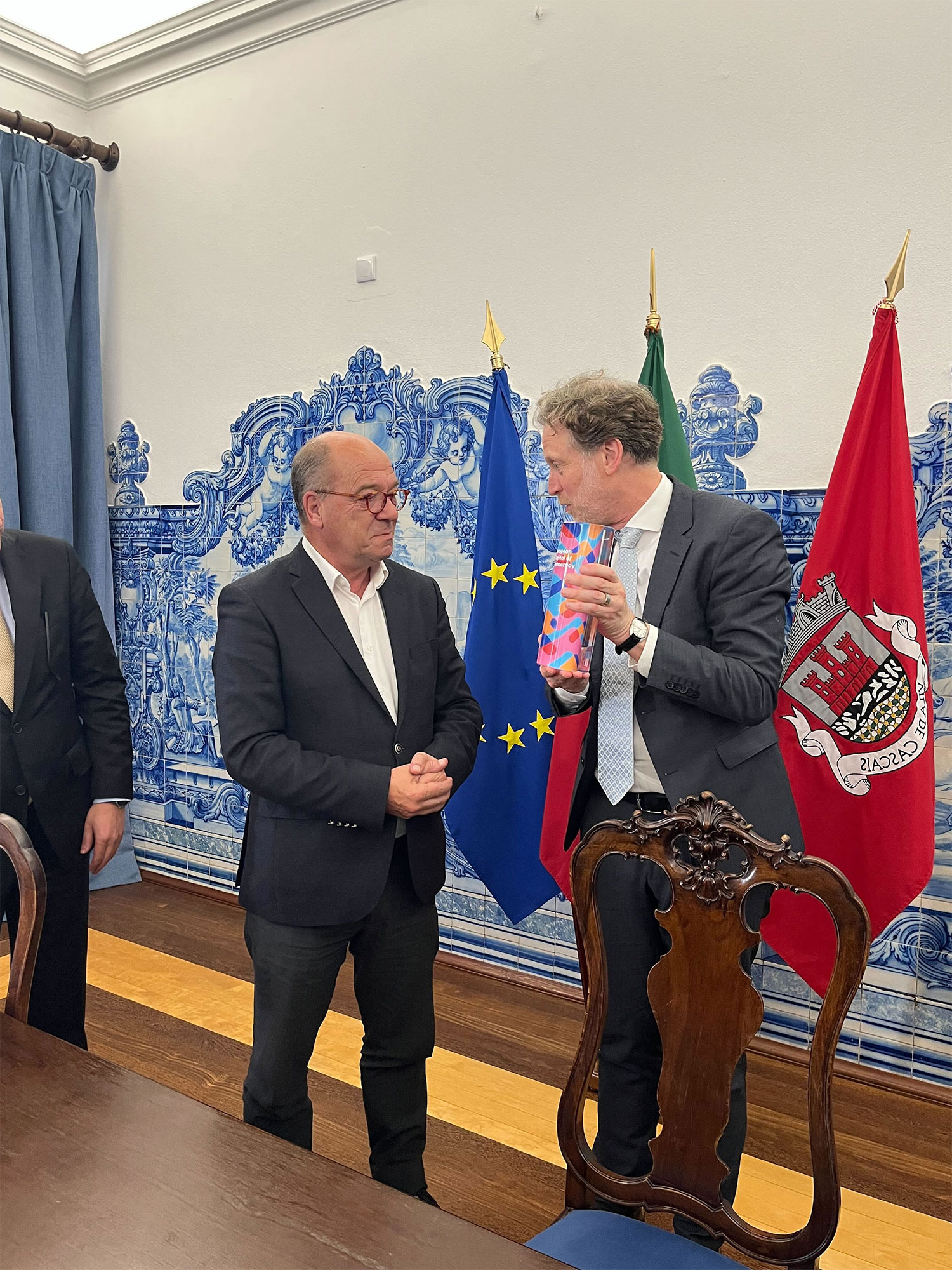

Round table discussion at the launch of the European Capital of Democracy initiative (upper left to lower right): Jürgen Czernohorszky, Aleksandra Dulkiewicz, Hermano Sanches Ruivo, Rafał Trzaskowski, Gergely Karácsony, Dubravka Šuica, Helfried Carl, Kostas Bakoyannis, Zdeněk Hřib, Matúš Vallo, Uta Zeuge-Buberl

This text will deal with the political responsibility of citizens and their involvement in new forms of political participation. In our upcoming article we will analyse the role of local governments and administrations in processes that enable political participation and civic engagement. A final blog entry will be dedicated to the city itself, as a space for encounter, communication as well as its inhabitants’ expression and realisation of common values.

We don’t mean “old style” participation

In the first round table discussion, Dubravka Šuica, European Commission Vice-President for Democracy and Demography, closed her statement by saying that “we are obliged to give citizens a greater say, and this is not only in words and theory”. She further highlighted that people have a genuine interest to engage in shaping their own communities. Jürgen Czerhorszky, Executive City Councillor in Vienna, added that there is a need, especially in bigger cities, to continuously debate and negotiate how we want to live together. Therefore, citizen participation can no longer be seen as a mere question-answer-forum between politicians and citizens. “Democracy is about getting people actively involved,” Czernohorszky further argued.

“we are obliged to give citizens a greater say, and this is not only in words and theory”

Dubravka Šuica, European Commission Vice-President for Democracy and Demography

This opinion was shared by all panelists who are all undertaking new forms of participatory democracy in their cities. Their initiatives pay credit to the political responsibility shared by all people residing in cities, irrespective of their nationality, age, political affiliation, or eligibility to vote. Becoming actively involved in political debates that have a direct impact on our daily lives can help to strengthen our democratic values. After all, the city is our shared living space. The more people take on an active role in shaping it, the better.

New forms of participatory democracy

Citizens’ assemblies or councils are great examples of deliberative democracy. They allow people of all ages and from different socio-economic and cultural backgrounds to find consensus in face-to-face debates (e.g. the Environmental Citizen Panel in Warsaw, Poland; the Citizens’ Assembly in Dublin, Ireland), either dedicated to a specific topic or to a wide range of policies. Meaningful encounters and discussions like these do not occur in an every-day context. Therefore, local governments have to create the necessary structures and finally facilitate such events. The Climate Assembly in the Hungarian capital Budapest for example allows citizens to define priorities for Budapest’s new climate policy. A civic lottery selects 50 representatives of the city’s residents (diverse in gender, age, socio-economic background, etc.) who develop a climate strategy together with experts and civil society organisations. The Assembly is regularly provided with information as a basis of discussion. Gergely Karáscony, Lord Mayor of Budapest, argues that such initiatives can help to find solutions for complex issues. Instead of overwhelming a majority of citizens with complex information, a group of representatives can find consensus that is acceptable to the majority.

The Mayor of Athens, Kostas Bakoyannis, introduced a new project which seeks to promote democracy in a city where “democratic values are deeply ingrained in the citizen’s DNA”: the Grand Walk of Athens. This multi-year project encourages citizens to reimagine public space and help determine priorities for the city government. The Grand Walk will finally connect Athen’s historic neighborhoods to the archeological sites of the city. With its 6 kilometres in length, the path will enable new and creative concepts of a versatile use of public space. It aims to diminish the accumulation of heat in the city centre caused by climate change, and it will allow for sustainable mobility.

Citizens should have the right to decide when, how and where they want to participate in political debates and decision-making. Therefore, many cities and communities all over the world are following the track of digital democracy. Digital tools can provide a direct way for people to communicate with the local government and administration about issues directly affecting the city’s residents. Apps like zmente.to, launched by the city of Prague in the Czech Republic, enable people to actively contribute to make their city a better place. Through the app, they can easily inform local authorities about problems regarding infrastructure and public spaces. This saves time and the impact is immediately measurable. Other digital platforms such as Söz Senin (Your Say), implemented by the city of Istanbul in Turkey, are more than just a tool for easing communication between the municipality and its citizens. People have the opportunity to answer surveys on a wide range of topics and therefore help to prioritise discussions and demands for local decision making.

The importance of best practice exchange

One of the goals of the European Capital of Democracy initiative is to discuss tools which help to evolve democracy in our cities. Thus, the initiative aims to motivate city leaders and city residents to exchange ideas and know-how, as both sides can greatly benefit from it. In his round table statement, Rafał Trzaskowski, Mayor of Warsaw in Poland, emphasised the importance of sharing successes and failures regarding the use of specific tools and methods to learn what works and what does not to bring about positive development more effectively.

The best practices presented above show that when citizens take an active role in their cities, democratic values are strengthened. Face-to-face encounters in debates, such as local citizens’ councils automatically create forms of respect towards the other who might hold a different view but has the same interest in living in a peaceful and prosperous society. Sometimes we lose in a debate about a policy that should be implemented, or our project idea that seeks funding will not be adopted in a participatory budget convention, where citizens can vote for projects proposed by other citizens. At the end of the day, a meaningful discourse, driven by mutual respect will guide us in finding consensus. That is democracy by definition.