Constantin Grosch understands that disability has political power. “Everyone is disabled once in their life. You always will have times in life when you encounter barriers and depend on others,” he shared during his webinar with our ACT NOW Mayors’ Network, aptly titled “Inclusion as a Driver of Innovation”.

From a very young age, Grosch made the active choice to work on breaking down the barriers that hinder people with disabilities. But in his late twenties, moreso on the background of the Covid-19 crisis, he found himself at a critical point to help normalise political decision-making that relieves the social, economic and healthcare pressures disabled people live with. He was involved in the recent legal reform (Bundesteilhabegesetz) of the rights of disabled people as a critic, advocate and advisor in the legislative process and founded AbilityWatch e.V., one of Germany’s most influential platforms for constructive disability rights activism. His work factors into the crucial changes that need to happen so that inclusion issues move forward from mere talk into actionable measures.

In this interview, Grosch opens up about the need for representation of people with disabilities in political bodies, the best ways to foster education and lower prejudice on what disability actually means, and collaborative behavior across communities in order to enable political measures that enhance inclusion.

In the webinar with the ACT NOW Mayors’ Network, you touched on disability as something that will happen to anyone, throughout their life, not just in the physical sense. How can we do a better job at framing disability in the socio-political context, so that it is recognised for its broad and diverse spectrum and integrated into everyday life?

Constantin Grosch: The most important lesson for the whole of society is that disabilities aren’t the result of a fault or the sole responsibility of an individual. Disabilities are natural and affect us all in some way or another. Anybody can be disabled in certain situations and most of us will be disabled for a period of our lives. Therefore, rebuilding our society in an inclusive and accessible fashion should not be framed as a charitable act of kindness but rather as a basic requirement to allow and activate action for and by the society.

Please share with us the circumstances of your journey into activism. What has changed since you started getting involved?

Constantin Grosch: Actually, I somewhat accidentally became an activist. When I finished highschool and became a law student I started to question the social welfare system in Germany. You have to understand that to present day disabled people in Germany who need a certain amount of help – for example personal assistance – are required to give up most of their earnings and wealth to pay for the assistance. So why should I even study?, I asked myself. Of course there is more to life than just making money and that is why I started a small petition with the goal of educating my friends and family. However, in the end the petition gained more than 300,000 supporters all over Germany and I found myself in the situation of having to explain the situation of disabled people in general and what demands we have. It was the beginning of a big campaign and even political action by the German parliament. Still, we didn’t succeed – or to put it in better terms: we were at least able to prohibit the politicians from taking away some of our hard-fought-for rights.

What positive change have you noticed and what do we still need to work at?

Constantin Grosch: Positive change can be seen in a higher degree of sensitivity in civil institutions. But the best part for sure are the new possibilities for the disabled community thanks to social media and the Internet. Today we are able to be visible to a larger audience just by acting on our own. I think there is a huge new generation of disabled people in Europe and in the world who know what possibilities lie ahead and what they can demand from society.

How do you experience the Covid-19 pandemic as a person with disability and as an activist?

Constantin Grosch: To be honest, I was and still am a bit shocked about how we deal with the pandemic in regards to people with disabilities. I admit that I was afraid about how quickly we debated if and how we should take action to save old and vulnerable people in a renowned German newspaper. I always believed that at least with our history in Germany we wouldn’t go back to these kinds of debates. But this shows you that you never can take progress for granted.

In the beginning there was a shortage of accessories for respiratory equipment for longtime users, because suppliers stopped delivering to individuals. Until today many important medical facilities, for example sleep laboratories, are closed or at least limited for non-emergency treatment. For patients with progressive disabilities these check-ups and treatments are very important to maintain their physical abilities for as long as possible.

When the German secretary of health announced the first priority list for vaccinations he completely forgot to mention disabled people under the age of 80. We had to lobby for more than three months to change this. Health experts and politicians were completely unaware that many disabled people in Germany nowadays do not live in institutionalised care facilities but live perfectly independent lives in their own homes with the assistance required. This led to widespread problems for these people, because they had no access to testing possibilities or were not entitled to get hygiene supplies for their caretakers.

To be quite frank: it all was and is a big mess. The only upside is my hope that for some decision makers this is a wake-up call. But my experience leads me to doubt that.

How do you perceive your life as an advocate for inclusivity?

Constantin Grosch: First of all, it is a deeply satisfying work. Not only do I help myself, but I can help thousands of people and can be sure that my work will enable future generations to live up to more of their own potential. It’s just a good feeling to know it is right what I do and right for what we fight for. On the other hand I can’t neglect the fact that sometimes it can be really frustrating. Not only do I hear heartbreaking stories of disabled people who do not get the help they need and literally break down because of it. But the progress of society and especially in politics is – sorry for swearing – damn slow. We do not have a lack of knowledge or a lack of technological possibilities to make our society more inclusive and accessible. And still it takes decades just to convince decision makers to act in the interest of all of us. Just their change of mind doesn’t mean that real-life barriers evaporate overnight.

To give you a small impression: for over eight years now we have been fighting for regulations for taxis. In Germany we do not have wheelchair-accessible taxis even in the biggest metropolitan areas. You have to reserve the few accessible taxis days ahead. This year they finally introduced a regulation that requires taxi companies to have five percent of their fleet be accessible. But only when they have more than twenty cars. That means that in rural areas you will not find any accessible taxis. When looking to London for example, every – I repeat – every taxi has had to be wheelchair accessible by law for ages. Something like that frustrates me a lot and I can be certain that patience is needed to be an activist. However a little bit of anger in your stomach isn’t bad either.

What challenges and surprises can you share?

The biggest challenge for an activist, especially a disability rights activist, is the financial side. Most charities only fund certain projects for a limited amount of time and usually no project that is strongly political. Political lobbying therefore is almost only possible as a volunteer or it needs to be paid for by working for other fundable projects at the same time. And here it gets tricky: because people with disabilities have it more difficult to find jobs anyway, only very few people can afford to be “full time”, professional activists.

What are things that people with disabilities are always confronted with that are constantly overlooked? What are people with disabilities tired of being told?

Constantin Grosch: The obvious answer would be barriers and prejudices. Especially prejudices are something that all disabled people are used to experiencing. Prejudice prevents society from recognising even our most basic skills and needs. We are often seen as asexual, unemployed and either overly joyful or terribly saddened people. But that’s far from the truth. We are just ordinary people. We are doctors, lawyers, politicians, actors, nurses or accountants and our lives and ambitions are just “normal”. We also want to achieve the children’s-book dream of living in our own little house, with a loving partner, a fairly paid job, a nice weekend evening in a cinema or a vacation once in a while. But instead we are constantly surrounded by people who want to put us in special care facilities, try to “protect” us from a “scary” education or work environment and talk about “special needs”. We do not have “special” needs. It is true: some of us need assistance or tools, but as humans we have the same life goals and social needs as everyone else.

People with disabilities are experts in using their limited resources to the fullest. We are trained by society to plan ahead and still be able to improvise within a moment’s notice. It’s that way because barriers constantly make us change our life and our plans.

Disabled people are ideal for checking in advance if an idea works in all its details, if people really benefit from it or if your solution is a sustainable one.

What are the biggest benefits for involving people with disabilities into decision-making in municipalities?

Constantin Grosch: First of all it enables you to identify problems early on. Everything that is a barrier for disabled people is at least a hassle or inconvenience for everybody. Often we experience that administrations or politicians offer services, organise events or build infrastructure that then rarely or never get used. But we only see the result, when it is too late, when the event was held, when the process is implemented or the building is set in stone. Disabled people are ideal for checking in advance if an idea works in all its details, if people really benefit from it or if your solution is a sustainable one. Yes, sometimes it is a challenge to make something suitable for disabled people. But when you achieve it, you can be sure it works for everyone else too.

Another good reason is that it forces your administration to develop new ideas and solutions. You can’t just “do what we always did” and you really have to go out “on the street” so to speak, to get information from disabled people in your community. Therefore, it is a good starting point for a participation orientated workflow and assessment tool. Obviously you also become more sustainable. A solution that works for all does not need multiple individual solutions or constant revisions.

We are ordinary people. We are doctors, lawyers, politicians, actors, nurses or accountants and our lives and ambitions are just “normal”. We also want to achieve the children's-book dream of living in our own little house, with a loving partner, a fairly paid job, a nice weekend evening in a cinema or a vacation once in a while.

What are the best ways to educate ourselves about the specific needs of people with disabilities in our communities and participate in creating space for them through valid solutions?

Constantin Grosch: First of all talk to disabled people in your community. I can guarantee you that they have already organised themselves in one way or another. It is very important to talk to the disabled people directly. Don’t fall into the trap and speak to people who claim to speak in their names. Why not invite different people with disabilities into your office and have an honest conversation about what you could do better or what ideas they might have.

As I already said: disabled people are masters in using limited resources to the fullest and they know that resources are not unlimited. There are also nation-wide disabled advocates out there in many countries who desperately try to reach out to politicians and decision makers.

For me another lesson is worth mentioning: the better you get at involving disabled people and addressing their needs, the more barriers you will see – not less. That is okay and should be that way. At the moment disabled people are kept out of many areas of our society. Therefore neither you nor they know what barriers and problems might be in place in those areas. But when we gradually make these spaces more accessible for everybody, the more we will see these hidden barriers. We have to learn to see these developments as a sign of our progress and as a constant push to take in new perspectives and information.

If you were mayor, what three concrete measures would you implement in your city?

Constantin Grosch: I would start by initiating a campaign for creating barrier free access to shops and services. Small barriers can and should be resolved by shop owners and companies themselves. For small or new businesses I would establish a sustainable fund that not only helps make businesses climate-neutral but also would fund measures to reduce barriers. Also, I would do a thorough assessment of the state of accessibility in my municipality in cooperation with local disabled people organisations (DPOs). Lastly, I would negotiate with state authorities to implement personal assistance and personal budgets for disabled people. I am convinced that people with disabilities themselves can decide much better than a public welfare agency about how to use the money we now spend for care and special facilities to achieve their goals and to participate in our society.

Continue reading

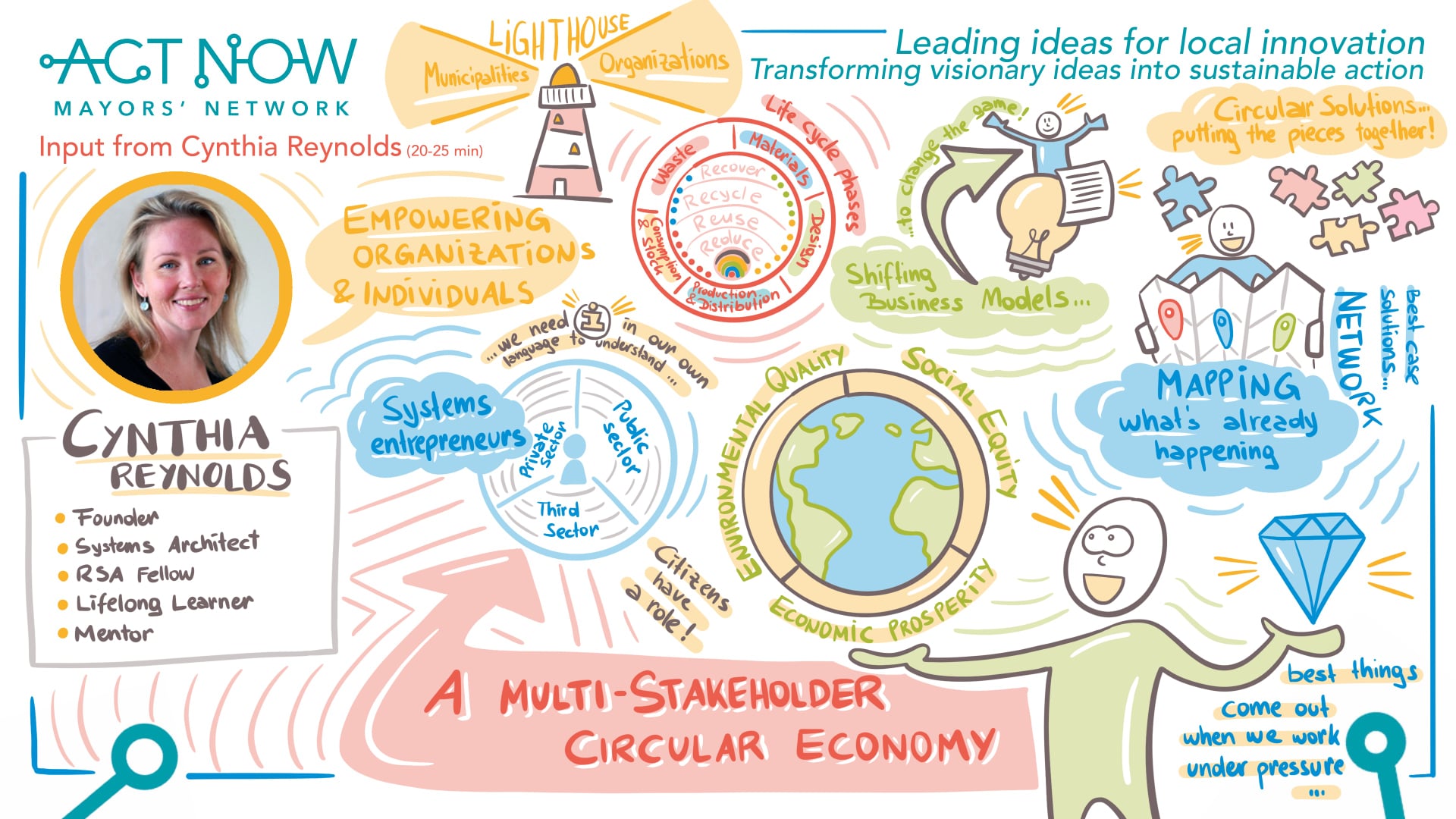

Circling back to the benefits of a Circular Economy